Beaky’ Bus. The backstory continued

What could go wrong? The Military ‘Travel moratorium’ of 1980. That’s what went wrong.

No sooner had I been recruited into the RAF – to become an Officer in the Physical Education Branch, trained and qualified as an Adventurous Training specialist tasked with and expected to introduce and develop Servicemen and women using the many challenges offered by the medium of the great outdoors – than a dictate came down from the people up there that ‘all units were to – ‘Tighten our belts.’ suddenly, this was a time when, as the Uk staggered through an economic crisis called the ‘winter of discontent.’ Amongst many elements of austerity savings from the Public Sector were required. There was a directive that no Public Funds were to be spent on non-essential travel including any for non-Military Operational requirements.

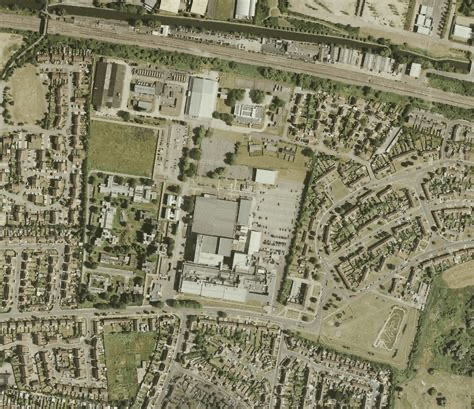

As a consequence, on my first posting to RAF West Drayton – an Airforce base comprising only a 250 square metres of land, hemmed tightly within a high security fence within an urban sprawl close to Heathrow Airport. With 1500 young service personal, the Station lacked any outside facilities; there wasn’t even a football pitch. Conducting any form of physical activity, adventurous or otherwise was difficult. Even running on the roads was discouraged as it risked attracting the attention of the IRA, a constant threat and a real objective risk at the time. Mountain walking, climbing or canoeing seemed to me a remote prospect.

RAF West Drayton

Our unit, I discovered did have access to some limited (what were called) non-public funds designed for activities that ‘enhanced the lives of serving personnel’ and the station Commander encouraged me to be creative and try to devise any activities that I could to divert and involve the younger personnel on the unit. His anxiety was that unoccupied, personnel would gravitate towards the many local bars and exposed to the risk of drugs that were inevitably on offer close by. Deploying these non-public funds, I had something to work with and recognised fully that I would need to husband them carefully in order to offer and fund at least some of the ‘exciting opportunities for adventure’ that all RAF recruitment centres and posters promised.

We did manage some expeditions and a significant success for me developed during that first restricted-travel summer of 1980. Our scuba diving club mounted an expedition to Islay off the west coast of Scotland. I took part as one of the diving supervising staff. We carried the expedition members and all the huge amount of kit required to Scotland using the Unit’s only resource, a Nuffield Grant funded minibus and a trailer that I purchased. One member of the expedition and I, for whom there was no space in the van, followed behind riding my old motorbike, a 1957 BMW.

The expedition was a great success due almost entirely to the extraordinary excellence of the SNCO Diving Club leader. I saw how he established a camp far from any civilisation in that wild, remote island, and Iwatched him repeatedly demonstrate great ingenuity and resourcefulness helping and challenging his charges to rise to the many challenges conducting a dive programme under such unhelpful circumstances. He accommodated, fed, trained and dive-supervised brilliantly. He demonstrated to me exactly what it was that some year previously, far-sighted leaders had hoped for, sought, anticipated and expected from expedition training. This wisdom (long ago) by some senior officer who must have persuaded the Service Chiefs of the day to encourage and direct some public funding towards this type of activity. I don’t now even recall the SNCO’s name, but I’m indebted to him. He created for me a guiding star. He showed me the way.

Riding my Motorcycle south towards London 400 miles away at the end of the diving adventure, my pillion and I rode miserably in heavy rain. We were wet through. I realised that on our route south from from Edinburgh along the A1 we would pass within 2 miles of the farm upon which two years previously I had abandoned my old bus.

After its jaunt with the 27 boys around Europe, it had occasionally served my rugby well but not a lot. On a whim I turned right from the main road and minutes later pulled up beside my old friend, the scruffy little bus. It looked as anyone would imagine it might after sitting without moving in the corner of a farmyard for a couple of years. It didn’t look promising. I climbed on board, sat in the driving seat and placed my hands on the so familiar, almost Flat, bus steering wheel. With little expectation I pressed the starter and instantly the engine started, without hesitation. It was sign.

For a few minutes I considered the potential for future expeditions such as I was returning from, had we the use of this old bus. The members and all of their diving and personal equipment could have been accommodated easily. Further, I thought, the many off-unit playing fields to which we had to travel routinely almost every day and goodness knows what else recreationally, could be made more easily accessible if we used this old bus. My farmer friend, the pillion expedition member (whose name also escapes me) and I lifted my old motorbike almost chest high and slid it into the bus through the rear emergency door and – I don’t recall whether this is actually true or not – I think I recall an illegal tankful of red diesel from his farm, before, in continuous rain we continued south, basking now in the warmth from my old chum’s heater as we slowly dried.

What could go wrong.

Chatting together as we buzzed down the A1 then across the M18 to the M1 and south towards London. I must have considered the wisdom of approaching such a long journey in a vehicle that had lain abandoned and unused for a couple of years, not to mention the risk I ran in driving such a conspicuously and unprepossessingly tatty old coach – with neither tax or insurance.

The challenge that actually concerned me most I do recall was, how to complete the final 100 metres of the journey. Arriving in the middle of the night at the main gate and guards when we approached RAF West Drayton. I faced the task of talking my way past the MoD Police. They were habitually unsympathetic to their uniformed colleagues. They manned the gate and controlled all access to the Unit. How would they react to my arrival in at 3am in an old and extremely unmilitary-looking bus. My pillion riding partner I had discussed this challenge at length as we cruised.

‘Well, I’ll just have to talk my way in,’ I had declared, and noticed that, by his expression, my companion thought, ‘rather me than him.’

I did achieve entry, not sure how but I did and then confronted my next challenge. I knew that it would be essential that I be outside my Boss’s door as he arrived on the station in a few hours, ready to explain my idea to him before the Station Commander or anyone else raised the question, ‘what’s that heap of junk that’s been left on the Unit carpark?’

What could go wrong.

More to come.

Leave a comment